Wednesday, November 30, 2005

Abstinence Only Sex Ed

This summary is not available. Please

click here to view the post.

Evidence of Common Descent between Man and Chimp

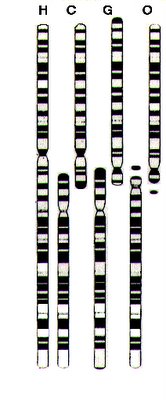

(H=human, C=chimp, G=Gorilla, O=orangutan)

Long long ago, in a laboratory far far away, scientists figured out that chimpanzees have 24 chromosomes in their sperms and eggs, whereas humans only have 23. Therefore, these great scientists theorized that two of our chromosomes might have fused together sometime in the recent past (aka million years ago.). Their theory made 3 predictions:

1) One of our chromosomes would look like two of the chimp chromosomes stuck together.

2) This same chromosome would have an extra sequence in it that looked like a centromere. Centromeres are the things in the middle that microtubules grab onto to divide a pair of chromosomes during mitosis.

3) It would also have telomeres (ends) but in the middle - and they would be in reverse order. Sort of like this:

ENDchromosomestuffDNEENDchromosomestuffDNE

See the "DNEEND" in the middle? That's what two telomeres would look like if two chromosomes were stuck together.

--From an excellent post by scigirl on IIDB.

As you might have guessed, all three predictions have been verified. While, as always, it's impossible to prove that an all-powerful being didn't create the evidence to trick us, the reasonable explanation is that humans and chimps share a common ancestor.

Tuesday, November 29, 2005

Wacky Bible Quote of the Day: Deu 25:11-12

Deu 25:11 When men strive together one with another, and the wife of the one draweth near for to deliver her husband out of the hand of him that smiteth him, and putteth forth her hand, and taketh him by the secrets:

Deu 25:12 Then thou shalt cut off her hand, thine eye shall not pity [her].

(images from The Brick Testament, previously mentioned here.)

Sunday, November 27, 2005

No Easy Answers

For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong. --H. L. Mencken

Good questions outrank easy answers. --Paul Samuelson

I was having a conversation with a friend recently and we were discussing why so many Americans possess so many simplistic religious beliefs. Eventually, we came to the conclusion that people just want easy answers. I think it's understandable -- life can be bewildering and overwhelming in the best of circumstances -- but it's leading to a very ignorant populace, which rejects, almost 200 years after Darwin, evolution.

Atheism and the more sophisticated theologies are hard.

When a dear friend dies, the simple theist can believe that his friend's in Heaven, surrounded by angels and loved ones. The skeptic must reconcile himself to the sad reality that his friend is just gone.

When the simple theist wonders how we got here, he can be satisfied with "And the LORD God formed man of the dust of the ground." The skeptic must find an introductory text on evolution. If he really wants to understand, he can spend his whole life studying genetics, biology, and paleontology, and still, at the end, not fully know.

When the simple theist has a moral dilemma, she may simply consult her rabbi, or open the Good Book. The skeptic must agonize, pondering ramifications and trade-offs, never knowing if her choice was "correct."

The simple theist believes that he and all of us are here for a very specific purpose. The skeptic must create his own meaning, or accept that perhaps there is none.

It takes courage to look past the easy (and wrong) answers and accept life's inherent complexity and unknowableness. I think the road less traveled is well worth the difficulty, however. The simple theist's world is small and simplistic, while the skeptic's is majestic and full of wonderful avenues of exploration. There is much we will never know, but we skeptics get to spend our lives learning all we can.

Q&A with the Jewish Atheist

While I was on vacation, I missed several questions by commenters. I figured answering them would be a good way to get back into blogging.

Q: Esther asks, [H]ow many of your friends growing up have left Modern Orthodoxy and where did they go? How often do you think this occurs? Do you think that insular groups have a higher retention rate than others?

A: I would estimate that approximately 20% of my modern Orthodox high school class are no longer Orthodox. Some are completely secular while some have moved to more liberal forms of Judaism like Conservative Judaism and the new "egalitarian," which is essentially Orthodox without the gender segregation.

Q: Anonymous asks, regarding thanksgiving, "Who are you thanking???"

A: First, I am thankful towards all of the people who have helped me or others, directly or indirectly. Second, I am just thankful (without being thankful TO someone) for the people and things in my life.

Q: R10B says, "This idea of the gov't getting out of the marriage biz (and other such matters) would be a great topic on it's own rather than hiding under a Evolution/ID heading. Who want's to take the party to their house? Or are you interested JA?"

A: I'm not sure I want to get into it in detail, but I would answer that the ship has sailed. We can't undo the government's involvement in marriage. Marriage has become both a religious and a secular institution. I agree that many of the problems today stem from people's confusing of and conflating the two, but I think the solution is to allow gay marriage without forcing any religious institution to recognize or perform same-sex marriage. This type of distinction already exists. For example, the state recognizes a marriage between a Jew and a Christian, while Orthodox Judaism doesn't have to.

Q: Esther asks, [H]ow many of your friends growing up have left Modern Orthodoxy and where did they go? How often do you think this occurs? Do you think that insular groups have a higher retention rate than others?

A: I would estimate that approximately 20% of my modern Orthodox high school class are no longer Orthodox. Some are completely secular while some have moved to more liberal forms of Judaism like Conservative Judaism and the new "egalitarian," which is essentially Orthodox without the gender segregation.

Q: Anonymous asks, regarding thanksgiving, "Who are you thanking???"

A: First, I am thankful towards all of the people who have helped me or others, directly or indirectly. Second, I am just thankful (without being thankful TO someone) for the people and things in my life.

Q: R10B says, "This idea of the gov't getting out of the marriage biz (and other such matters) would be a great topic on it's own rather than hiding under a Evolution/ID heading. Who want's to take the party to their house? Or are you interested JA?"

A: I'm not sure I want to get into it in detail, but I would answer that the ship has sailed. We can't undo the government's involvement in marriage. Marriage has become both a religious and a secular institution. I agree that many of the problems today stem from people's confusing of and conflating the two, but I think the solution is to allow gay marriage without forcing any religious institution to recognize or perform same-sex marriage. This type of distinction already exists. For example, the state recognizes a marriage between a Jew and a Christian, while Orthodox Judaism doesn't have to.

Saturday, November 19, 2005

Happy Thanksgiving!

I won't be posting much if any until next weekend, so a happy Thanksgiving to all who celebrate!

Friday, November 18, 2005

Conservative Columnists Turning Against the Christian Right

When conservatives George Will and Charles Krauthammer have op-eds in the same week critical of some Republicans, you know the tide is shifting. Both are dismayed by the hijacking of the Republican party by fundamentalists who want our public schools to teach "Intelligent Design" as part of the science curriculum. Here are their words:

Krauthammer:

Will:

* "anodyne," a word I'd never heard before, means "serving to assuage pain."

(It appears that I will continue to debate, although I'll try to remain as civil as possible. :) )

Krauthammer:

Let's be clear. Intelligent design may be interesting as theology, but as science it is a fraud. It is a self-enclosed, tautological "theory" whose only holding is that when there are gaps in some area of scientific knowledge -- in this case, evolution -- they are to be filled by God. It is a "theory" that admits that evolution and natural selection explain such things as the development of drug resistance in bacteria and other such evolutionary changes within species but also says that every once in a while God steps into this world of constant and accumulating change and says, "I think I'll make me a lemur today." A "theory" that violates the most basic requirement of anything pretending to be science -- that it be empirically disprovable. How does one empirically disprove the proposition that God was behind the lemur, or evolution -- or behind the motion of the tides or the "strong force" that holds the atom together?

In order to justify the farce that intelligent design is science, Kansas had to corrupt the very definition of science, dropping the phrase " natural explanations for what we observe in the world around us," thus unmistakably implying -- by fiat of definition, no less -- that the supernatural is an integral part of science. This is an insult both to religion and science.

The school board thinks it is indicting evolution by branding it an "unguided process" with no "discernible direction or goal." This is as ridiculous as indicting Newtonian mechanics for positing an "unguided process" by which Earth is pulled around the sun every year without discernible purpose. What is chemistry if not an "unguided process" of molecular interactions without "purpose"? Or are we to teach children that God is behind every hydrogen atom in electrolysis?

He may be, of course. But that discussion is the province of religion, not science. The relentless attempt to confuse the two by teaching warmed-over creationism as science can only bring ridicule to religion, gratuitously discrediting a great human endeavor and our deepest source of wisdom precisely about those questions -- arguably, the most important questions in life -- that lie beyond the material.

How ridiculous to make evolution the enemy of God. What could be more elegant, more simple, more brilliant, more economical, more creative, indeed more divine than a planet with millions of life forms, distinct and yet interactive, all ultimately derived from accumulated variations in a single double-stranded molecule, pliable and fecund enough to give us mollusks and mice, Newton and Einstein? Even if it did give us the Kansas State Board of Education, too.

(Source. Hat tip: respondingtojblogs.)

Will:

The storm-tossed and rudderless Republican Party should particularly ponder the vote last week in Dover, Pa., where all eight members of the school board seeking reelection were defeated. This expressed the community's wholesome exasperation with the board's campaign to insinuate religion, in the guise of "intelligent design" theory, into high school biology classes, beginning with a required proclamation that evolution "is not a fact."

But it is. And President Bush's straddle on that subject -- "both sides" should be taught -- although intended to be anodyne*, probably was inflammatory, emboldening social conservatives. Dover's insurrection occurred as Kansas's Board of Education, which is controlled by the kind of conservatives who make conservatism repulsive to temperate people, voted 6 to 4 to redefine science. The board, opening the way for teaching the supernatural, deleted from the definition of science these words: "a search for natural explanations of observable phenomena."

"It does me no injury," said Thomas Jefferson, "for my neighbor to say there are twenty gods, or no God. It neither picks my pocket nor breaks my leg." But it is injurious, and unneighborly, when zealots try to compel public education to infuse theism into scientific education. The conservative coalition, which is coming unglued for many reasons, will rapidly disintegrate if limited-government conservatives become convinced that social conservatives are unwilling to concentrate their character-building and soul-saving energies on the private institutions that mediate between individuals and government, and instead try to conscript government into sectarian crusades.

(Source)

* "anodyne," a word I'd never heard before, means "serving to assuage pain."

(It appears that I will continue to debate, although I'll try to remain as civil as possible. :) )

Thursday, November 17, 2005

This Needs to Change

Be the change that you want to see in the world. --Gandhi

Everyone thinks of changing the world, but no one thinks of changing himself. --Tolstoy

The situation described in my last post (and an unrelated, rather heated email exchange which ended with somebody threatening me) has made me do some thinking. Why is it that so many of us (including myself, of course) spend our energy blaming everybody but ourselves? We spend so much time criticizing instead of seeking common ground and figuring out a way to work together. It's just like politics on the national scale. The two sides get so worked up about a few emotional issues that they ignore almost everything else. Hardly anybody tries to put themselves in their opponent's shoes, but instead assumes that their opponents are not just wrong, but stupid and/or evil.

We confuse the means with the ends. I say I argue about religion because I value science and progressive values, but there must be more effective ways to advance those ends than all this arguing.

I'm not sure I want to continue arguing about religion. In the best case, I'll convince a few people that religion isn't true and causes some problems, but even then I'm also contributing to the hatred on both sides.

I think that some people (like politicians) divide us on purpose, knowing that if they can keep us arguing about gay marriage and abortion, we won't notice when they're fleecing the public and passing measures that the majority of Americans wouldn't support if they had all the information. I want to say that because I think it's true, but then I think maybe I'm just criticizing again instead of seeking to improve things myself.

So I'm going to change. I'm just not sure how.

Wednesday, November 16, 2005

Why Doesn't the Religious Right Support Universal Health Care?

A friend of mine recently met a retired nurse in her sixties. She has diabetes along with a host of other medical problems. She's one of the ones that Democrats talk about when they tell us stories of people having to choose between buying medicine and buying food. She can't get all the medicine her doctor believes she needs because Medicare doesn't cover it, and she can only eat vegetables for the first week or two of the month, because she simply can't afford more. This is not a lazy woman. She worked for decades as a nurse and can no longer work due to her health problems.

We're the richest country in the world.

Democrats have been pushing for universal health care for decades, but have been stymied by Republicans who think the money would be better spent with more tax cuts for multi-millionaires. If not universal health care, how about just more health care? Why do we let children go uninsured?

Which side of this debate would Jesus have been on?

We're the richest country in the world.

Democrats have been pushing for universal health care for decades, but have been stymied by Republicans who think the money would be better spent with more tax cuts for multi-millionaires. If not universal health care, how about just more health care? Why do we let children go uninsured?

Which side of this debate would Jesus have been on?

Quote of the Day - Religion and Heredity

Out of all of the sects in the world, we notice an uncanny coincidence: the overwhelming majority just happen to choose the one that their parents belong to. Not the sect that has the best evidence in its favour, the best miracles, the best moral code, the best cathedral, the best stained glass, the best music: when it comes to choosing from the smorgasbord of available religions, their potential virtues seem to count for nothing, compared to the matter of heredity. --Richard Dawkins

Almost every religious person will tell you that their religion is the most logical, the most accurate, and has the best moral code. And yet the great majority of them were born into their religion and hardly considered any of the others. And a majority of the ones who picked a religion other than their parents', picked the one belonging to most people who live near them. It's as rare to find someone in Alabama who decided that Zoroastrianism is correct as it is to find a Bantu tribesman who decided that Judaism is true.

Monday, November 14, 2005

More Demographic Fun, or Red State "Values" Don't Work

Did you know that the Red States have:

A higher divorce rate? Liberal, secular Massachusetts, with its scary gay marriage, has the lowest. Texas has almost twice as many divorces per capita. More fun facts: Bob Barr, the Republican who wrote the "Defense of Marriage Act", has been married three times. Baptists have the highest divorce rate. Tell me, whom does marriage really need defending from?

Higher teen pregnancy rates? Massachusetts has a rate of 7.4, while Texas's is 16.1. I wonder why the Blue States aren't rushing out to copy abstinence-only sex-ed.

Less education? At least Kansas is taking decisive action by inserting intelligent design into the curriculum.

More money coming in than going out with taxes? Why do they keep complaining about taxes then?

We need to move away from "faith-based" values and towards "evidence-based" values. Maybe if the Red States started paying more attention to the data and less to simplistic ideology, they'd start to close the gap.

(Some of these data are from this article.)

A higher divorce rate? Liberal, secular Massachusetts, with its scary gay marriage, has the lowest. Texas has almost twice as many divorces per capita. More fun facts: Bob Barr, the Republican who wrote the "Defense of Marriage Act", has been married three times. Baptists have the highest divorce rate. Tell me, whom does marriage really need defending from?

Higher teen pregnancy rates? Massachusetts has a rate of 7.4, while Texas's is 16.1. I wonder why the Blue States aren't rushing out to copy abstinence-only sex-ed.

Less education? At least Kansas is taking decisive action by inserting intelligent design into the curriculum.

More money coming in than going out with taxes? Why do they keep complaining about taxes then?

We need to move away from "faith-based" values and towards "evidence-based" values. Maybe if the Red States started paying more attention to the data and less to simplistic ideology, they'd start to close the gap.

(Some of these data are from this article.)

Religions of the World

Isn't it weird how people in different parts of the country can be so wrong about what God wants?

People in other countries are REALLY far off.

There are a lot of misinformed people out there.

(Sources: http://www.adherents.com/maps/US_denom_cong.jpg, http://wps.prenhall.com/wps/media/objects/412/422174/05fig01.gif, http://www.adherents.com/Religions_By_Adherents.html)

People in other countries are REALLY far off.

There are a lot of misinformed people out there.

(Sources: http://www.adherents.com/maps/US_denom_cong.jpg, http://wps.prenhall.com/wps/media/objects/412/422174/05fig01.gif, http://www.adherents.com/Religions_By_Adherents.html)

Saturday, November 12, 2005

Is God an Accident?

This is the religion-as-accident theory that emerges from my work and the work of cognitive scientists such as Scott Atran, Pascal Boyer, Justin Barrett, and Deborah Kelemen. One version of this theory begins with the notion that a distinction between the physical and the psychological is fundamental to human thought. Purely physical things, such as rocks and trees, are subject to the pitiless laws of Newton. Throw a rock, and it will fly through space on a certain path; if you put a branch on the ground, it will not disappear, scamper away, or fly into space. Psychological things, such as people, possess minds, intentions, beliefs, goals, and desires.

Paul Bloom, a Yale professor of psychology and linguistics, has a fascinating article in this month's The Atlantic Monthly: "Is God an Accident? (Subscribers only, unfortunately.) Bloom hypothesizes that belief in the supernatural arises from the fact that we have essentially two cognitive systems which work together. When we think about inanimate objects like stones or baseballs, we use one cognitive system; when we think about people or dogs, we use another.

Bodies and Souls

Understanding of the physical world and understanding of the social world can be seen as akin to two distinct computers in a [person]'s brain, running separate programs and performing separate tasks...

For those of us who are not autistic, the separateness of these two mechanisms, one for understanding the physical world and one for understanding the social world, gives rise to a duality of experience. We experience the world of material things as separate from the world of goals and desires. The biggest consequence has to do with the way we think of ourselves and others. We are dualists; it seems intuitively obvious that a physical body and a conscious entity—a mind or soul—are genuinely distinct. We don't feel that we are our bodies. Rather, we feel that we occupy them, we possess them, we own them...

This belief system opens the possibility that we ourselves can survive the death of our bodies. Most people believe that when the body is destroyed, the soul lives on. It might ascend to heaven, descend to hell, go off into some sort of parallel world, or occupy some other body, human or animal. Indeed, the belief that the world teems with ancestor spirits—the souls of people who have been liberated from their bodies through death—is common across cultures. We can imagine our bodies being destroyed, our brains ceasing to function, our bones turning to dust, but it is harder—some would say impossible—to imagine the end of our very existence. The notion of a soul without a body makes sense to us.

Bloom refers to a study in which scientists showed children a story about a mouse which was eaten by an alligator:

As predicted, when asked about biological properties, the children appreciated the effects of death: no need for bathroom breaks; the ears don't work, and neither does the brain. The mouse's body is gone. But when asked about the psychological properties, more than half the children said that these would continue: the dead mouse can feel hunger, think thoughts, and have desires. The soul survives. And children believe this more than adults do, suggesting that although we have to learn which specific afterlife people in our culture believe in (heaven, reincarnation, a spirit world, and so on), the notion that life after death is possible is not learned at all. It is a by-product of how we naturally think about the world.

We've Evolved to be Creationists

Then Bloom gets to the good stuff:This is just half the story. Our dualism makes it possible for us to think of supernatural entities and events; it is why such things make sense. But there is another factor that makes the perception of them compelling, often irresistible. We have what the anthropologist Pascal Boyer has called a hypertrophy of social cognition. We see purpose, intention, design, even when it is not there.

In 1944 the social psychologists Fritz Heider and Mary-Ann Simmel made a simple movie in which geometric figures—circles, squares, triangles—moved in certain systematic ways, designed to tell a tale. When shown this movie, people instinctively describe the figures as if they were specific types of people (bullies, victims, heroes) with goals and desires, and repeat pretty much the same story that the psychologists intended to tell.

Stewart Guthrie, an anthropologist at Fordham University, was the first modern scholar to notice the importance of this tendency as an explanation for religious thought. In his book Faces in the Clouds, Guthrie presents anecdotes and experiments showing that people attribute human characteristics to a striking range of real-world entities, including bicycles, bottles, clouds, fire, leaves, rain, volcanoes, and wind. We are hypersensitive to signs of agency—so much so that we see intention where only artifice or accident exists. As Guthrie puts it, the clothes have no emperor.

Our quickness to over-read purpose into things extends to the perception of intentional design. People have a terrible eye for randomness. If you show them a string of heads and tails that was produced by a random-number generator, they tend to think it is rigged—it looks orderly to them, too orderly. After 9/11 people claimed to see Satan in the billowing smoke from the World Trade Center. Before that some people were stirred by the Nun Bun, a baked good that bore an eerie resemblance to Mother Teresa. In November of 2004 someone posted on eBay a ten-year-old grilled cheese sandwich that looked remarkably like the Virgin Mary; it sold for $28,000. (In response pranksters posted a grilled cheese sandwich bearing images of the Olsen twins, Mary-Kate and Ashley.) There are those who listen to the static from radios and other electronic devices and hear messages from dead people—a phenomenon presented with great seriousness in the Michael Keaton movie White Noise. Older readers who lived their formative years before CDs and MPEGs might remember listening intently for the significant and sometimes scatological messages that were said to come from records played backward.

Bloom admits that "We are not being unreasonable when we observe that the eye seems to be crafted for seeing, or that the leaf insect seems colored with the goal of looking very much like a leaf," but goes on to say, "Darwin changed everything. His great insight was that one could explain complex and adaptive design without positing a divine designer. Natural selection can be simulated on a computer; in fact, genetic algorithms, which mimic natural selection, are used to solve otherwise intractable computational problems. And we can see natural selection at work in case studies across the world, from the evolution of beak size in Galápagos finches to the arms race we engage in with many viruses, which have an unfortunate capacity to respond adaptively to vaccines."

What's the Problem with Darwin?

What's the problem with Darwin? His theory of evolution does clash with the religious beliefs that some people already hold. For Jews and Christians, God willed the world into being in six days, calling different things into existence. Other religions posit more physical processes on the part of the creator or creators, such as vomiting, procreation, masturbation, or the molding of clay. Not much room here for random variation and differential reproductive success.

But the real problem with natural selection is that it makes no intuitive sense. It is like quantum physics; we may intellectually grasp it, but it will never feel right to us. When we see a complex structure, we see it as the product of beliefs and goals and desires. Our social mode of understanding leaves it difficult for us to make sense of it any other way. Our gut feeling is that design requires a designer—a fact that is understandably exploited by those who argue against Darwin.

It's not surprising, then, that nascent creationist views are found in young children. Four-year-olds insist that everything has a purpose, including lions ("to go in the zoo") and clouds ("for raining"). When asked to explain why a bunch of rocks are pointy, adults prefer a physical explanation, while children choose a functional one, such as "so that animals could scratch on them when they get itchy." And when asked about the origin of animals and people, children tend to prefer explanations that involve an intentional creator, even if the adults raising them do not. Creationism—and belief in God—is bred in the bone.

Bloom's Conclusion

Religious teachings certainly shape many of the specific beliefs we hold; nobody is born with the idea that the birthplace of humanity was the Garden of Eden, or that the soul enters the body at the moment of conception, or that martyrs will be rewarded with sexual access to scores of virgins. These ideas are learned. But the universal themes of religion are not learned. They emerge as accidental by-products of our mental systems. They are part of human nature.

Thursday, November 10, 2005

The Affirmations of Humanism: A Statement of Principles

I'm not yet a member of the Council for Secular Humanism, but I seem to agree with most of their principles. That's a rare and precious thing when you're a skeptic and an atheist.

- We are committed to the application of reason and science to the understanding of the universe and to the solving of human problems.

- We deplore efforts to denigrate human intelligence, to seek to explain the world in supernatural terms, and to look outside nature for salvation.

- We believe that scientific discovery and technology can contribute to the betterment of human life.

- We believe in an open and pluralistic society and that democracy is the best guarantee of protecting human rights from authoritarian elites and repressive majorities.

- We are committed to the principle of the separation of church and state.

- We cultivate the arts of negotiation and compromise as a means of resolving differences and achieving mutual understanding.

- We are concerned with securing justice and fairness in society and with eliminating discrimination and intolerance.

- We believe in supporting the disadvantaged and the handicapped so that they will be able to help themselves.

- We attempt to transcend divisive parochial loyalties based on race, religion, gender, nationality, creed, class, sexual orientation, or ethnicity, and strive to work together for the common good of humanity.

- We want to protect and enhance the earth, to preserve it for future generations, and to avoid inflicting needless suffering on other species.

- We believe in enjoying life here and now and in developing our creative talents to their fullest.

- We believe in the cultivation of moral excellence.

- We respect the right to privacy. Mature adults should be allowed to fulfill their aspirations, to express their sexual preferences, to exercise reproductive freedom, to have access to comprehensive and informed health-care, and to die with dignity.

- We believe in the common moral decencies: altruism, integrity, honesty, truthfulness, responsibility. Humanist ethics is amenable to critical, rational guidance. There are normative standards that we discover together. Moral principles are tested by their consequences.

- We are deeply concerned with the moral education of our children. We want to nourish reason and compassion.

- We are engaged by the arts no less than by the sciences.

- We are citizens of the universe and are excited by discoveries still to be made in the cosmos.

- We are skeptical of untested claims to knowledge, and we are open to novel ideas and seek new departures in our thinking.

- We affirm humanism as a realistic alternative to theologies of despair and ideologies of violence and as a source of rich personal significance and genuine satisfaction in the service to others.

- We believe in optimism rather than pessimism, hope rather than despair, learning in the place of dogma, truth instead of ignorance, joy rather than guilt or sin, tolerance in the place of fear, love instead of hatred, compassion over selfishness, beauty instead of ugliness, and reason rather than blind faith or irrationality.

- We believe in the fullest realization of the best and noblest that we are capable of as human beings.

Wednesday, November 09, 2005

Goodbye Not The Gadol Hador

The man with maybe the best frum skeptic's blog out there, Not The Gadol Hador, is closing up shop. (Again.) As I mentioned in my first post ever, his blog was a large part of the reason I started my blog. Although I haven't been spending too much time over there lately, I always read his posts. I will miss him.

Republicans and Factual Relativism

Introduction

Republicans like to accuse the left of "moral relativism."Well, I'm here to accuse them of "factual relativism." By this I mean that they don't care about facts. You may provide facts, but they will ignore, twist, and deny. They will never provide facts of their own, simply providing ever-retreating statements until they find something that isn't falsifiable (but has no basis in fact) or else repeating the lie over and over again.

Minor Example

I just had a dispute with Sadie Lou over at her place when she claimed that yesterday's California election came down, among other things, to "Christians vs. non-Christians." You can read it yourself, or you can enjoy this reenactment:Me: But a majority of Democrats are Christians, too. Here's proof.

Her: Maybe for the rest of the country, but not for California.

Me: But a majority of Californian Democrats are also Christian. Here's proof.

Her: They aren't real Christians. They probably don't go to church, believe that Jesus died on the cross, or read their Bibles, and think that bombing abortion clinics and beating up gays is okay.

Me: They do go to church (here's proof) but I don't have data on the rest of it.

Her: Aha! I was right.

Political Examples

Kansas just decided to change the definition of the word "science" because Intelligent Design doesn't fit into the actual definition of science.The Bush administration distorts scientific research. For example, they "sought changes in an Environmental Protection Agency climate study, including deletion of a 1,000-year temperature record and removal of reference to a study that attributed some of global warming to human activity" when the facts didn't agree with them on global warming.

Tuesday, November 08, 2005

My Experience with Buddhism

Believe nothing, no matter where you read it, or who said it, no matter if I have said it, unless it agrees with your own reason and your own common sense. -- Buddha

Introduction

When I left Orthodoxy, I spent some time reading up on other religions. Buddhism, coming from an entirely different tradition, taught me a lot of stuff I hadn't really thought about before. It's particularly appealing to me as a skeptic and an atheist because, although there are many dogmatic Buddhists, there has been an anti-dogmatic aspect to Buddhism since the beginning. Buddhism, or at least the kind of Buddhism I'm attracted to, is empirical, albeit not as formally as science. Additionally, as a Western Jew, I am under no societal or familial pressure to accept Eastern claims which conflict with science, so I may comfortably pick and choose among Buddhism's ideas. Interestingly, so many American Jews are drawn to Buddhism that a term, "Ju-Bu," has been coined to describe them. I suspect that this happens because Buddhism contains values -- like iconoclasm, liberalism, and a reluctance towards violence -- that many American Jews share and find lacking in the stricter forms of Judaism in America.A Note on Buddhism and Skepticism

Being a skeptic, an atheist, and an empiricist, I cannot simply believe in far-out claims like reincarnation, chi, and spiritual karma without evidence. However, I have found that many Eastern ideas, when viewed metaphorically, make enough sense to be useful.Disclaimer

I am not a Buddhist. This post is about my experience of Buddhism and Yoga and probably does not accurately represent the views of actual Buddhists and Yogis.The Practice is the Philosophy

Buddhism has its sacred texts, which I have so far ignored, but it also has a number of practices with which you can learn simply by doing. The fundamental practice of Zen, a kind of Buddhism, is meditation.How to Meditate

Here's what I do. Sit or lie comfortably. Be aware of your breath. Watch as thoughts arise in your brain. Don't get lost in them. Realize that "you" are not your thoughts. Your thoughts arise by themselves. Watch as emotions arise. Realize that "you" are not your emotions. This is more or less mindfulness meditation. There are many other kinds of meditation.No Self

One of the most important ideas of Buddhism is that the self is an illusion, that we are all part of the Divine. I am you is the rock are God. It is from our false belief that we are individuals that arises all of our suffering. Because we think we are separate, we grasp. Because we grasp, we are always unsatisfied. We want a bigger house, a beautiful object, or a smile from a loved one. When we sit in meditation, we come to realize that "we" are not our wants.This idea of "no-self" meshes interestingly with science. Empirically, it appears that what we consider "I" is an emergent phenomenon of the complexity of neural interactions in the brain. Fundamentally, we are made of the same stuff as a rock or a star. Furthermore, experiments show that decisions are made in our brains before we are conscious of making a decision, casting doubt on the very existence of free will. The Buddhist idea of "no-self," at this point, cannot be said to be definitively true, but it also cannot be disproved. You might think that I would object to the notion of the Divine, as an atheist, but I believe that the Divine in Buddhism is more-or-less equivalent to "the universe" or "existence" in Western thought. It's commonly believed that many Buddhists can be reasonably called atheists as well.

What I Have Learned from Buddhism

I have learned about the importance of being present. Once you get a taste for meditation, it can affect how you relate to the world. When I am present, I experience heightened sensation, a deep calm, and positive emotions towards all Beings. (It's difficult to talk about spirituality without being cheesy or using cliches. However, anybody may try meditation and see for themselves. No God and no faith are required.) When I am present, I am less likely to engage in hurtful behavior like overeating, arguing too much online, procrastinating, or otherwise distracting myself from life. I enjoy having things not going my way more while being mindful than I do having things go my way when I'm not being mindful. As an example, waiting in line while being mindful is more enjoyable than eating great food while not paying attention.I have also learned to see that people who do great destruction often do so because they fall to this grasping that Buddhism teaches about. I always wondered why millionaires like Ken Lay, the CEO of Enron, would engage in illegal and unethical behavior simply to make more money he couldn't possibly need. The answer is that people who think of themselves as totally separate always think they need more and that they can take it at the expense of other people. He probably thinks that if he can just make another $100 million, he'll be happy. I can see him as a lost, sad human being rather than just as a caricature of evil. People numb themselves (which is the opposite of being mindfully present) to the damage they are doing to themselves and others.

Resources

Buddhism, Taoism, and Yoga touch on many of the same ideas. I recommend learning about any of them.Zen and the Art of Motorcycle maintenance was my introduction to Zen Buddhism, as it is for so many young Westerners. It's not really about Buddhism, but it's very readable and is likely to whet your appetite, particularly if you tend to intellectualize.

Wherever You Go, There You Are : Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life, by Jon Kabat-Zinn, who runs the very well-respected Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Guided Mindfulness Meditation is a great 4-CD secular introduction to meditation also from Jon Kabat-Zinn.

A.M. and P.M. Yoga for Beginners is a great introduction to the practice of yoga, which is another form of meditation. I also recommend Crunch: The Perfect Yoga Workout.

Mindfulness In Plain English is a free, online book.

Tara Brach has some very interesting speeches available online for free. I also recommend her book, Radical Acceptance : Embracing Your Life with the Heart of a Buddha.

Infinite Smile is an intellectual Buddhist podcast.

Meditations from the Mat is a deep book by a former college football player, Army Ranger, and recovered addict. My Christian readers might want to start with this, since the author is a devout Christian. I think it's great and I've read it at least twice, a couple of pages a day.

The Book : On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are is an amazing blow-your-mind experience from the British scholar Alan Watts. Many of Watts's speeches are available online if you look around.

Go Vote! Bring your friends! Your parents! Your neighbors!

Don't let the extremists (who are much more likely to vote) have all the power.

Monday, November 07, 2005

Baloney Detection Kit

How can we tell the difference between rational claims and baloney claims? In The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark the late Carl Sagan writes:

(I copied the text from this website, but it's a pull from the book.)

The following are suggested as tools for testing arguments and detecting fallacious or fraudulent arguments:

* Wherever possible there must be independent confirmation of the facts

* Encourage substantive debate on the evidence by knowledgeable proponents of all points of view.

* Arguments from authority carry little weight (in science there are no "authorities").

* Spin more than one hypothesis - don't simply run with the first idea that caught your fancy.

* Try not to get overly attached to a hypothesis just because it's yours.

* Quantify, wherever possible.

* If there is a chain of argument every link in the chain must work.

* "Occam's razor" - if there are two hypothesis that explain the data equally well choose the simpler.

* Ask whether the hypothesis can, at least in principle, be falsified (shown to be false by some unambiguous test). In other words, it is testable? Can others duplicate the experiment and get the same result?

Additional issues are

* Conduct control experiments - especially "double blind" experiments where the person taking measurements is not aware of the test and control subjects.

* Check for confounding factors - separate the variables.

Common fallacies of logic and rhetoric

* Ad hominem - attacking the arguer and not the argument.

* Argument from "authority".

* Argument from adverse consequences (putting pressure on the decision maker by pointing out dire consequences of an "unfavourable" decision).

* Appeal to ignorance (absence of evidence is not evidence of absence).

* Special pleading (typically referring to god's will).

* Begging the question (assuming an answer in the way the question is phrased).

* Observational selection (counting the hits and forgetting the misses).

* Statistics of small numbers (such as drawing conclusions from inadequate sample sizes).

* Misunderstanding the nature of statistics (President Eisenhower expressing astonishment and alarm on discovering that fully half of all Americans have below average intelligence!)

* Inconsistency (e.g. military expenditures based on worst case scenarios but scientific projections on environmental dangers thriftily ignored because they are not "proved").

* Non sequitur - "it does not follow" - the logic falls down.

* Post hoc, ergo propter hoc - "it happened after so it was caused by" - confusion of cause and effect.

* Meaningless question ("what happens when an irresistible force meets an immovable object?).

* Excluded middle - considering only the two extremes in a range of possibilities (making the "other side" look worse than it really is).

* Short-term v. long-term - a subset of excluded middle ("why pursue fundamental science when we have so huge a budget deficit?").

* Slippery slope - a subset of excluded middle - unwarranted extrapolation of the effects (give an inch and they will take a mile).

* Confusion of correlation and causation.

* Straw man - caricaturing (or stereotyping) a position to make it easier to attack..

* Suppressed evidence or half-truths.

* Weasel words - for example, use of euphemisms for war such as "police action" to get around limitations on Presidential powers. "An important art of politicians is to find new names for institutions which under old names have become odious to the public"

(I copied the text from this website, but it's a pull from the book.)

Sunday, November 06, 2005

Was Man Created Before or After the Animals?

An oldie but goodie:

Therefore, the Bible is not literally true.

Version 1

1:25 And God made the beast of the earth after his kind, and cattle after their kind, and every thing that creepeth upon the earth after his kind: and God saw that it was good.

1:26 And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth.

1:27 So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.

Version 2

2:7 And the LORD God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul...

2:18 And the LORD God said, It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him an help meet for him.

2:19 And out of the ground the LORD God formed every beast of the field, and every fowl of the air; and brought them unto Adam to see what he would call them: and whatsoever Adam called every living creature, that was the name thereof.

Therefore, the Bible is not literally true.

Friday, November 04, 2005

Is God Moral?

It ain't those parts of the Bible that I can't understand that bother me, it is the parts that I do understand. --Mark Twain

Assumptions

Let's assume for the sake of argument that the God of the Bible does exist. How can we determine whether it's moral to obey Him?If one defines "moral" as "whatever God says," then it's tautological that we must obey. So let's assume that "moral" means something else, something that most of us basically agree on even if we can't articulate. Something based fundamentally on human empathy for each other and, to a lesser extent, for other animals.

If "moral" isn't defined as "whatever God says," but we know that God is all-good and all-knowing then we must obey Him nevertheless. However, if we know that god is not all-good or that He is not all-knowing, then we must question whether obeying Him is moral. It's possible, after all, that God is evil, that He created us in order to amuse himself with earthquakes and war.

Let's stipulate that He is all-knowing, or at least that He knows more than we do, since this would be true of any reasonable definition of God.

The Question

The only question remaining is, is God all-good? Since we're working from the assumption that the word "moral" is not synonymous with "whatever God says," we must use some criteria for deciding whether God is moral, and judge Him by His words and actions.The Evidence

Since the God we are discussing is the God of the Bible, then we have his words, and if we believe that God created the Universe, we have his actions. Can we prove that God is all-Good from either of these two sources? I don't think so -- each provides material which at least raises doubts. In the Bible, God commands animal sacrifice, he kills every person and animal on Earth except those allowed into Noah's Ark, orders the killing of anyone who violates the Sabbath, orders the killing of blasphemers, orders the killing of the Midianite women and children and "taking" of their virgins, the killing of worshipers of other Gods, the killing of non-virginal brides, etc. (Find these and more at the Skeptic's Annotated Bible.)Similarly, the world, which He created, is full of suffering -- rape, murder, sickness, natural disasters.

Conclusion

It might be possible to justify the actions and orders found in the Bible and the horrible circumstances found in the world, but we must acknowledge that we cannot simply assume that God is all-good based on His Book or on the universe. Nor does any amount of goodness in the Bible or in the world exonerate God of his questionable words and actions -- a doctor who saves thousands of lives but cruelly murders his wife cannot be said to be all-good. It may be -- however unlikely it seems to me -- that God has some divine plan that makes everything that appears bad to us part of a larger good, but we cannot make this assumption without assuming what we are trying to prove -- that God is all-good.What are we left with? We cannot know for sure that God is all-good, so we cannot know for sure if following his commandments is moral. We must decide on a case-by-case basis what we shall follow and what we shall disobey.

In the absense of evidence of God's morality, I maintain that it is moral to disobey commandments which we deem immoral. If God spoke directly to me and told me to murder an innocent child, I would be forced to disobey. Similarly, I could not support Biblical laws which I believe immoral -- even assuming I believed in both God and the divinity of the Bible.

(Hat tip to Sadie Lou for suggesting this topic.)

Thursday, November 03, 2005

On Scientific Naturalism

Let’s start with a quick experiment. You can grab three coins and actually do the experiment, or just do a thought experiment.

Drop one coin and watch it fall. Do this again. Hold out the third coin.

If you were to do this again, what do you think would happen? If you could get ten good Christians to pray that this next coin wouldn’t fall, would it still fall? How about one thousand faithful Muslims? How about one billion people of any faith? I think that it would still fall. Drop the third coin.

Our understanding of the world around us, and our abilities to predict what will happen are based on naturalism -- the basis of science. Naturalism is how all people live their lives most of the time. --Why Atheism, by Mark Thomas

"Why Atheism" is a good primer on scientific naturalism and atheism.

Wednesday, November 02, 2005

What Does "Supernatural" Mean? or Splitting Hairs, Part III

"The invisible and the non-existent look very much alike." John Stuart Mill

I'm having a very interesting discussion with David over at Sago Boulevard about the word "supernatural." My argument is that it is a word that religious and superstitious people use to dodge the evidence that what they believe in doesn't exist.

Let's start with a basic definition. Nature is, according to the relevent definition in Merriam Webster's Online Dictionary, "the external world in its entirety." That's pretty much how I would define it as well. Supernatural, on the other hand, means (1) "of or relating to an order of existence beyond the visible observable universe; especially : of or relating to God or a god, demigod, spirit, or devil" or (2) "departing from what is usual or normal especially so as to appear to transcend the laws of nature b : attributed to an invisible agent (as a ghost or spirit.)"

We can toss out the second definition as irrelevant, because it's talking about appearences and attributions. The first I don't quite agree with, since nobody would call a galaxy so far away that we couldn't observe it "supernatural," although such a galaxy would fit this definition. So what do religious/superstitious people really mean by "supernatural?"

Maybe they mean "of or relating to an order of existence beyond the visible observable (even in theory) universe." This takes care of the parts of the universe that are too far away.

But if we carefully study even this revised definition, something will strike us. The word "beyond." "Beyond," according to m-w Online, means either (1) "on or to the farther side of : at a greater distance than," (2) "a : out of the reach or sphere of b : in a degree or amount surpassing c : out of the comprehension of," or (3) "in addition to : BESIDES."

Well, we've already ruled out 1 and 2a with our distant galaxy example. It seems like they must mean "beyond" in the sense of 2c or 3. Let's take them one at a time.

2c) Let's say that supernatural means "of or relating to an order of existence [out of [our] comprehension of] the visible observable (even in theory) universe." What does this mean? If the supernatural exists, even if we couldn't comprehend it, we should at least be able to observe it. Since when is observation limited by comprehension? I can observe a kid acting out "beyond" reality, meaning I can't comprehend how a human being could behave like that, but I'm still observing it. I can't comprehend in some senses the Big Bang, but I can still observe (indirectly) that it happened. I don't think we can use this sense of "beyond" to make "supernatural" mean anything.

3) Perhaps supernatural means "of or relating to an order of existence [in addition to or besides] the visible observable (even in theory) universe." This implies that supernatural beings reside someplace other than the universe. However, time and space are bound by the universe, so there is no "outside" the universe (or "outside" time.) Some scientists do hypothesise a "multiverse," where reality is made up of many universes, but it's a heavily criticed line of reasoning, and proponents of the "supernatural" surely don't mean "something that's natural, just in a different universe," anyway.

I'm left with the conclusion that "supernatural" doesn't mean anything more than "non-existent," or perhaps "fictional." In one sense, Huckleberry Finn could be said to exist, but I don't think that's what theists mean when they talk about the supernatural. "Supernatural" is a term applied to that which doesn't exist in an effort to make it seem like it does.

There's one more point I'd like to make, and that is that scientific claims are always extraordinarily detailed and concrete while religious ones tend to be vague and abstract. I think this is the case because detailed and concrete religious claims were too easily to disprove and the faithful have adapted. Now you'll very rarely see a falsifiable religious claim. (People raise the same objections about string theory, an area of exploration that many claim is not scientific because it's not falsifiable.)

Tuesday, November 01, 2005

How to Argue with Smart People, or Why I Like to "Split Hairs"

Smart people, or at least those whose brains have good first gears, use their speed in thought to overpower others. They’ll jump between assumptions quickly, throwing out jargon, bits of logic, or rules of thumb at a rate of fire fast enough to cause most people to become rattled, and give in. When that doesn’t work, the arrogant or the pompous will throw in some belittlement and use whatever snide or manipulative tactics they have at their disposal to further discourage you from dissecting their ideas. Scott Berkun

I believe this applies to many blog commentators, and not just the smart ones. They hop, skip, and jump from argument to argument and topic to topic, never letting you pin down the flaws because by the time you get there, they're already somewhere else.

Scott Berkun has some ideas about how to prevent people from doing this. Although he's talking mostly about working on a software development team, I think his advice is relevant to all of us.

So your best defense starts by breaking an argument down into pieces. When they say “it’s obvious we need to execute plan A now.” You say, “hold on. You’re way ahead of me. For me to follow I need to break this down into pieces.” And without waiting for permission, you should go ahead and do so.

First, nothing is obvious. If it were obvious there would be no need to say so. So your first piece is to establish what isn’t so obvious. What are the assumptions the other guy is glossing over that are worth spending time on? There may be 3 or 4 different valid assumptions that need to be discussed one at a time before any kind of decision can be considered. Take each one in turn, and lay out the basic questions: what problem are we trying to solve? What alternatives to solving it are there? What are the tradeoffs in each alternative? By breaking it down and asking questions you expose more thinking to light, make it possible for others to ask questions, and make it more difficult for anyone to defend a bad idea.

No one can ever take away your right to think things over, especially if the decision at hand is important. If your mind works best in 3rd or 4th gear, find ways to give yourself the time needed to get there. If when you say “I need the afternoon to think this over”, they say “tough. We’re deciding now”. Ask them if the decision is an important one. If they say yes, then you should be completely justified in asking for more time to think it over and ask questions.

I realize now that this technique is what I always try to do, but I've never spelled it out before. I try to keep the focus on a single aspect of an argument until it's settled. I don't let my opponent shift the goalposts, gloss over an assumption, or use fallacious logic in order to befuddle me.

The best part is that you can often (well, "rarely" is probably more accurate) convince your opponent that they need to rethink their position, since it's basically a house made with shoddy materials on a shaky foundation.

In his essay, he also includes the reasons he believes smart people defend stupid ideas: they inherited them from parents, they've gotten away with defending them before, groupthink, short-term thinking, desire for an idea to be true, following stupid leaders, etc.

I think religious people are particularly likely to hold bad ideas due to tradition, following stupid leaders, and the desire for an idea to be true.

Religion, Truth, and the Five Stages of Grief

Every great scientific truth goes through three stages. First, people say it conflicts with the Bible. Next they say it had been discovered before. Lastly they say they always believed it.

-- Louis Agassiz (Swiss naturalist, 1807-1873)

I have a slightly different theory. I think that when religion is confronted by truth that conflicts with their most basic beliefs, it goes through the stages of grief: Denial, Anger, Bargaining, Depression, Acceptance.

First, it denies it. The Earth doesn't go around the Sun. Evolution didn't happen.

Second, it gets angry. We'll burn you if you say the Earth goes around the Sun. We'll fight if you try to teach evolution in our schools.

Third, it bargains. Maybe the Earth just looks like it goes around the Sun. Maybe "Intelligent Design" is what happened.

Fourth, religious people get upset that a key part of their worldview has been proven false. Many leave.

Fifth, religion accepts the truth as its own. Of course the Earth goes around the Sun. Obviously evolution happened -- doesn't the Bible say that God created the plants before the fish before the land animals before the people?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)